Bainbridge Island, WA– Walking down Winslow Way among trendy shops, restaurants and art galleries, Bainbridge Island seems like any other over priced tourist destination, but dig a little deeper and what you find here may surprise you.

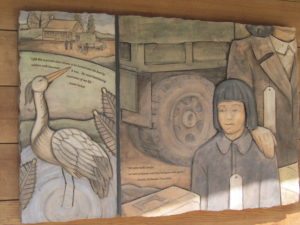

With recent efforts to ban Muslims from entering the country and talk of building a wall on our borders perhaps some lessons can be learned from what happened on this island 75 years ago. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 which led to the forced removal and incarceration of 120,000 Japanese Americans from the west coast. The first to go were Bainbridge Island’s 227 Japanese American residents on March 30, 1942. Led by armed guards into waiting boats, they were given only six days notice and allowed to bring only what they could carry. “I felt like a second class citizen. To be herded onto a boat with bayonets. It was the most humiliating experience of my life, ” recalled Isami Nakao, then 27.

Bainbridge Island’s Japanese American residents were the first group to be sent to Manzanar in California and were later assigned to Minidoka, Idaho. Since the 1880s, Japanese Americans had been an integral part of the island’s community. Working in lumber mills, strawberry farms and owning businesses. They lived and worked alongside immigrants from Finland, Austria, Italy, China, Croatia, Hawaii and the Philippines.

In 2010, a memorial wall was built on the historic Eagledale Ferry Dock honoring the names of all men, women and children who were exiled from their home. Future development on the site includes 150 foot departure pier, representing the 150 residents who returned to Bainbridge Island after the war and a 4000 square foot interpretive center that will explore the history of the event.

http://www.bijac.org/index.php?p=MEMORIALIntroduction

The Bainbridge Island Review was the only newspaper on the west coast to consistently oppose the internment of Japanese Americans. Published by Walt and Milly Woodward, the Woodwards even hired Japanese American high school students to report on their life behind barbed wire, including births, deaths, and other daily activities of exiled islanders. The Woodwards earned received many honors in their lifetime for the courageous stances they took during the war. A middle school on the island is named after them

Filipinos began arriving on the island in the 1920s and 1930s to work on Japanese owned strawberry farms. When Japanese Americans were forced to leave, many Filipino farmhands stepped up to save their crops and manage their farms while they were away in camps. First Nations people from Canada came to help with labor. Some Filipinos married First Nations women. Their offspring were called “Indopinos.” To learn more about the Filipino experience on Bainbridge Island visit the Filipino American Community Hall, 7566 N. E. High School Road which is one of several island sites listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

http://onecallforall.org/filipino-american-community-of-bainbridge-island-vicinity/

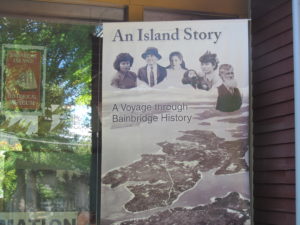

To learn more about the island’s history and it’s contributions from various immigrants visit the excellent Bainbridge Island Historical Museum, 215 Erickson Avenue N.E.

Getting to Bainbridge Island is easy. It’s a 30 minute ferry ride from Seattle. You can contact Washington State Ferries for information:

http://www.wsdot.wa.gov/ferries/

There are plenty of accommodations on the island if you’d like to spend the night. I got around by renting a bicycle from Bike Barn Rentals 260 Olympic Way S. E. , near the ferry terminal.

http://bikebarnrentals.com/